The Scratcher's Dickie

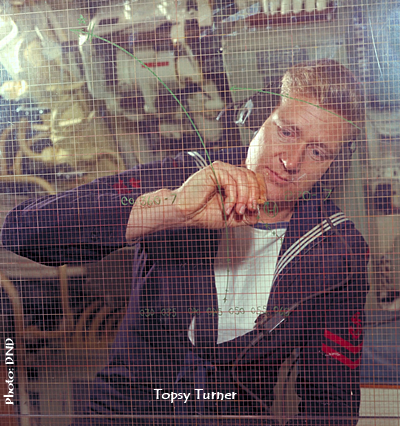

LSRP Ed 'Topsy' Turner! He was the "Scratcher" and I was "Scratcher's Dickie" when Ojibwa commissioned. Imagine that! I was the youngest and most outranked hand on board and already had a 2 I/C position in this 2-man team.

Incentive to Excel

Yup, Scratcher and Scratcher's Dickie were the common terms for the personnel "in charge" (I/C) and "2nd in charge" (2 I/C) of the casing. We looked after the maintenance and the appearance of the casing, fin and tank tops alongside. Topsy supervised the forward casing party and I supervised the after casing party at Harbour Stations. Everyone in the after casing party, all senior to me, knew what to do so I didn't have to say a thing. Or rather, I knew better than to say a thing. I got to go under the casing after all the lines were let go, to stow and secure them for sea. As I got better at it, I could have it done before we got too far out to sea and the water was washing in over my butt as I knelt crouched over to turn the hawsers up and lash them in on the stag horn stowage fittings. The after casing was lower to the water level and I always got wet back there, but as I got more proficient I could get it done before freezing solid in the sub-zero winter departures.

Casing Crawl

|

Topsy was a good boss who tried to teach me everything he knew about the casing and seamanship and Topsy allowed me to practice it all until I was an expert at it. When alongside maintenance was involved, he trusted me to the degree that he did not even appear on the casing to supervise. There was always a "casing crawl" prior to leaving harbour. That was, literally, a crawl through, in and around the maze of the fittings and equipment squeezed in under the casing, to ensure that there were no loose items or broken parts. Those things could cause serious noise or other problems at sea and dived where it would be impossible to correct them. One of the biggest problems was tools and junk left behind by stokers, dockyard matey and others working on equipment located under the casing. I was just a little guy so Topsy explained that it was best that I did the entire crawl because I could fit through all of the tight spots from stem to stern. What a guy! He always recognized my strong points.

|

Topsy Trick

|

He also taught me the trick with lamp black and linseed oil. The CO and the XO always wanted Ojibwa to look good alongside and expected us to give it a fresh, even 'flat-black' appearance soon after getting alongside. Lamp black and linseed oil could be applied easily in just about any weather, dried fast, and looked good. I had it down pat.

With long-tom and thick nap roller I could finish it in less than three hours, doing the casing deck with the most traffic around the accommodation space hatch, brow, and forward of the fin after everyone else had gone ashore. Topsy told me that I was so good at it that he preferred not to interfere and he would just proceed ashore trusting that I would do an excellent job. What a great leader, showing so much confidence in his subordinates. |

Daunting Duty as Buoy Jumper

Topsy detailed me off for the daunting duty of buoy jumper. For various reasons, when we were patrolling in coastal waters, we often put up for the night in small bays and harbours where there were no jetty facilities alongside for us to moor.

We would either anchor out or moor to a buoy. On coming to a buoy, I would be wearing a life jacket, have a safety line attached around my waist, and have my 'jumper's tool bag' in hand. Someone was responsible for handling my safety line giving me the right amount of slack to allow me to do the job but not get in trouble. The CO would try to position the submarine as close to the buoy as possible so that I could jump, often a running jump, out and down onto the buoy. The huge barrel-like buoys had all sorts of painful protrusions in their construction, like the huge eye and ring for securing the anchor cable to, that I could grab onto when I landed. Sometimes the buoy was moving due to wave action or especially from the prop wash as the CO went full astern once reaching the buoy. Any miscalculation, by my safety line handler or me, meant that I could crash into the ring or completely miss grabbing hold.

Cormorant Crap

|

The buoys were often covered with a layer of ice and always covered with seagull and cormorant crap. That wasn't good. The buoy was always very, very slippery. Topsy said that, because I was light in stature, it would be much easier to recover me than it would be for one of the heavier guys, when I wound up in the water, which I often did. Part of the procedure involved securing the anchor cable to the ring of the buoy using a three piece joining shackle, taper pin and lead pellet hammered home with a ball peen hammer to prevent the taper pin from falling out. I had to perform those steps with bare hands to ensure I didn't drop any bits.

|

Don't try this at Home

|

In extreme cold weather my hands would hurt like hell in contact with the frozen metal parts. So, before I jumped, Topsy instructed me to soak my hands in the large coffee can full of diesel fuel that he brought up to the casing for that purpose. I don't understand the physical reaction but when I pulled my hands out to expose them to the frigid air it felt like they were on fire for a few seconds before they became completely numb. So there was no slow painful process while on the buoy. I wouldn't even feel it when I hit them with the hammer. What a man. He was always considering the safety and comfort of his people.

|

Fun Ramps Up - Buoys will be Buoys

Once I jumped and was planted solidly on the buoy, someone would pass me the ‘picking-up rope’ that I would secure to the ring of the buoy with a huge shackle.

Now this is where the fun could really ramp up. Normally I would be recovered, back to the casing, before heaving in on the picking up rope with the hydraulic capstan. However, if there was a strong wind, current or tide running, (and there was always at least one of these factors), the submarine could be forced away from the buoy while the casing party was giving me enough slack to secure the eye and shackle to the ring. In that case, which was most of the time, they would heave it in with me hanging on. In that situation there was always a tremendous strain on the picking-up rope and, subsequently, the entire system anchoring the buoy to the bottom. The buoy would invariably be hauled down sometimes completely submerging it.

Hang on! and Other Valuable Advice

|

On one of those extreme occasions the buoy was almost fully submerged and the picking-up rope was as taut as a bowstring and singing up a storm. Topsy was yelling at me to "hang on!" Duh! Like I needed supervision for that mission! They had heaved the buoy in to a distance of about ten feet from the boat when the picking-up rope parted with a sickening crack. The buoy leapt up out of the water like a bucking bronco, and Topsy yelled, "Jump!" So I did, trying to jump away from the boat so I wouldn't be trapped between it and the buoy.

|

At that very moment my safety-line handler decided to rescue me by pulling in sharply on my safety-line. I got yanked out of mid-air and swung rapidly toward the side of the boat.

Luck was with me though as the arc carried me into the water slowing my approach down just enough before I crashed into the side of the casing. It was only a mild collision but my weight plus that of my tool bag, that I refused to relinquish, pulled me deeper into the water before my line handler and a couple of others got a grip and pulled me to the surface and aft, around the starboard hydroplane, to an area that I could be hauled up onto the ballast tanks and then to the casing.

The CO decided to spend the night at sea.

The CO decided to spend the night at sea.

Arduous Conditions have Rewards

On a positive note, whenever I went into the water I would be issued a tot of rum for "arduous conditions". It's amazing how that tot fixed whatever ailed you but trying to hold onto that tot mug with numb hands was always a challenge. However, like any good submariner I never lost a drop. Justice Hawkins, the coxswain, always reminded me that the deal was off if it happened in tropical waters. We never went to a buoy in tropical waters. It was always the North Atlantic coastal areas.